Japan`s Security Posture and the Evolving Indo-Pacific Order

- Editorial Staff

- May 23, 2025

- 9 min read

A Narrative Geopolitical Study

Prepared: May, 2025

Author: Strategic Analysis Unit – CEPRODE EUROPE

Download the full report here:

Setting the Stage

Japan is experiencing a historic inflection point. At once cushioned and constrained by the seventy-year embrace of the United States, it now finds itself face to face with a People’s Republic of China that wields not only the world’s second-largest navy but also a sophisticated information apparatus intent on rewriting the rules of regional engagement. Meanwhile, a sanctions-isolated Russia, far from being deterred by setbacks in Ukraine, has rediscovered the strategic utility of its Pacific coastline and bomber arm. Overlaying these pressures is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, an unpredictable state whose missile tests serve as ambient thunder in the East Asian soundscape. Against this backdrop Tokyo has embarked on a quiet but profound transformation: it remains anchored to the American alliance, yet it weaves new strands of cooperation that stretch south to Australia, west to India, and, increasingly, across half the globe to Europe.

The pages that follow trace the long arc of this transformation, explore the multiple domains in which Japan must now operate—land, sea, air, cyber, space and, crucially, the cognitive and economic spheres—and sketch a series of forward-looking scenarios that extend to the middle of the next decade. Rather than presenting the material as a string of terse bullet points, the narrative style adopted here attempts to capture the momentum, the nuance and the interlocking causalities that define Japan’s strategic debate. Each section flows into the next, mirroring the way in which defence, diplomacy and domestic politics flow into one another inside the policymaking corridors of Nagata-chō.

From Pacifism to Proactive Posture: A Historical Narrative

Any attempt to understand contemporary Japanese strategy must begin in the ruins of 1945. The Yoshida Doctrine, named after Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, was less a grand design than a survival instinct: let the United States provide the hard shield while Japan, exhausted and resource-poor, rebuilt its economy behind that shield. In the decades that followed, Tokyo tipped the balance of its national energies toward industry, research and export prowess, paying for the protection of the U.S. Seventh Fleet not with troops but with Toyota sedans and Sony radios.

For most of the Cold War this bargain held, although the Soviet naval build-up in Vladivostok and missile deployments on the Kuril chain gnawed at Japanese planners. By the late 1980s the Maritime Self-Defence Force had quietly become one of the world’s most

capable anti-submarine navies, yet political ceilings kept defence spending below one per cent of GDP —a symbolic line suggesting that Japan, unlike the great powers of old, would never again place the sword at the centre of its identity.

The 1990s disrupted that equilibrium. During the Gulf War, Tokyo’s offer of chequebook multilateralism—thirteen billion dollars in cash but no troops—earned scorn in Washington and little gratitude in Kuwait City. North Korea’s 1998 Taepodong missile, arcing over Hokkaido into the Pacific, further punctured illusions of distance. These shocks gradually eroded constitutional scruples: legislation in 1992 permitted participation in UN peacekeeping, while the 2015 security bills, championed by the late Shinzo Abe, re-interpreted Article 9 to allow ‘collective self-defence’. By the time Fumio Kishida spoke of a ‘new realism diplomacy’ in 2022, Tokyo was ready to double defence spending and to speak openly of counter-strike capabilities—phrases once deemed politically radioactive.

The Contemporary Strategic Atmosphere

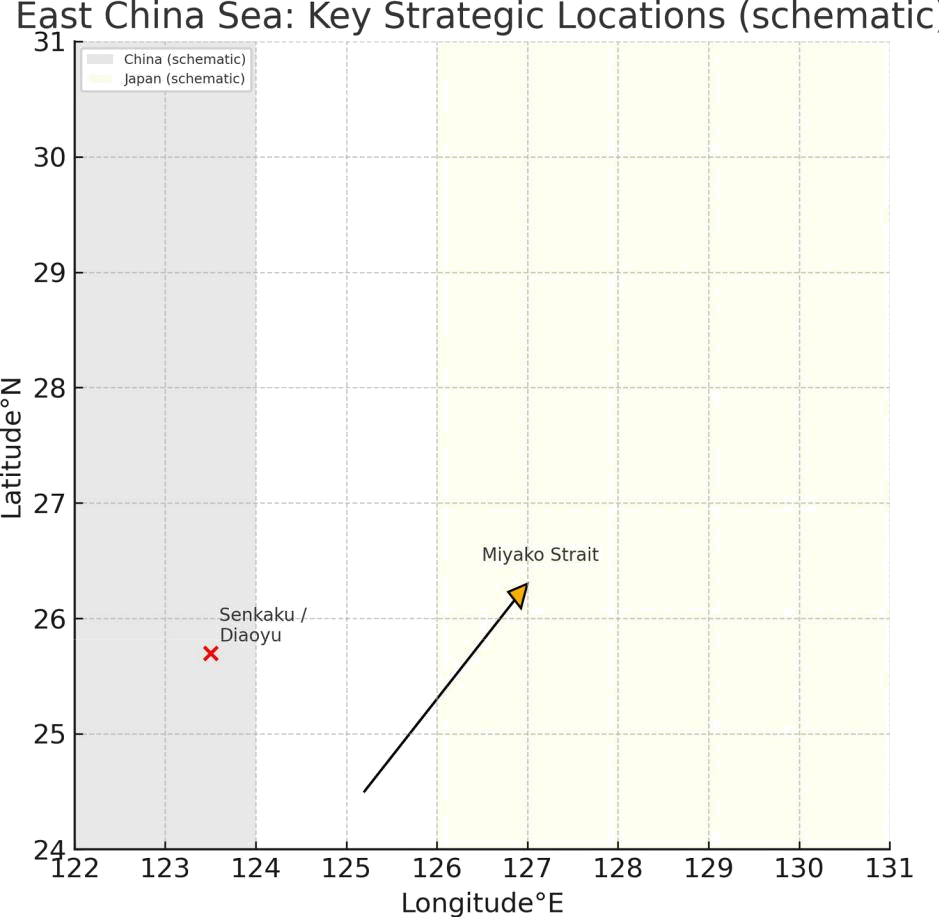

To walk the streets of Tokyo is to sense a paradoxical calm: the neon hum, the punctual trains, the annual surge of cherry blossoms. Yet beyond the horizon line, the waters grow crowded. Chinese coast-guard cutters linger around the Senkaku Islands, sometimes edging into Japan’s territorial sea with the deliberate slowness of someone testing a locked door. In the skies above, PLA bombers trace routes that loop first around Taiwan, then north toward Okinawa before turning for home over the Sea of Japan —an airborne geometry designed to remind observers of China’s expanding radius of confidence.

North Korea adds an element of dramaturgy: missiles hurtle into the Sea of Japan at irregular and deliberately unsettling intervals, each launch serving Pyongyang’s twin purposes of technological advancement and political signalling. Russia, for its part, has redeployed Tu-95 and Tu-142 aircraft to its Far-Eastern bases, and its Pacific Fleet, though modest in scale, has resumed joint bomber patrols with the Chinese air force. The combined effect is not simply military; it is psychological. It seeks to normalise encirclement, to wear away Japan’s sense of sanctuary.

At the same time, change is stirring inside Japan itself. After years of demographic decline and economic stagnation, the public is beginning to accept that an insurance premium of two per cent of GDP for defence is no longer excessive but prudent. The phrase ‘economic security’ has entered everyday political vocabulary, and ministries that once fought for bigger welfare budgets now compete for quantum-computing initiatives or stockpiles of critical minerals. Japan’s strategic horizon has widened from the strictly local—‘defend the homeland’—to the broadly systemic—‘shape the Indo-Pacific’. And shaping, in this context, means building coalitions.

Knots in the Lattice: Japan’s Expanding Constellation of Partners

Although the United States remains the fulcrum of Japanese security, the bilateral alliance is no longer a solitary pillar; it is the central knot in a growing network. The Quad, once dismissed as a talk-shop, now convenes naval drills that criss-cross half the Indian Ocean. AUKUS, initially about nuclear-powered submarines, has opened a second pillar that invites Japan to collaborate on cyber, quantum and autonomous undersea vehicles. In Europe, the United Kingdom and Italy have joined Japan in the ambitious Global Combat Air Programme—an endeavour that reaches beyond technology to weave

industrial ecosystems and classified data links.

These initiatives, varied in format and membership, share a single strategic logic: they make it harder for any adversary to isolate Japan in a crisis. An attack on one Japanese outpost could, in theory, implicate an Australian replenishment ship, a British F-35 squadron or an Indian maritime patrol aircraft. Deterrence thus acquires gradation and redundancy; it grows not heavier but more intricate, like a spiderweb capable of absorbing shocks by distributing them across multiple threads.

Instruments of Power: From Flight Decks to Data Streams

Capabilities are catching up with policy. On the ocean surface, two Izumo-class helicopter carriers have been refitted to host F-35B short-take-off fighters, their flight decks coated with heat-resistant material. Beneath the waves, the latest Taigei-class submarines, powered by advanced lithium-ion batteries, promise longer submerged endurance. In the air, airborne warning and control planes—E-2D Advanced Hawkeyes—extend Japan’s radar horizon, while ground-based Patriot batteries receive the PAC-3 MSE upgrade to swat missiles in their terminal phase. Across the electromagnetic spectrum, a nascent Joint Operations Command ties these nodes together, its screens glowing with fused feeds from radars, satellites and, soon, swarming unmanned systems.

The cyber and space domains, once peripheral, now anchor policy debates. A dedicated Cyber Command tracks thousands of intrusion attempts each day, many traced back to state-backed actors in neighbouring countries. In orbit, Japan’s Quasi-Zenith Satellite System not only augments GPS accuracy but also provides protected channels for the Self-Defence Forces. Perhaps most striking is the emergence of the ‘cognitive domain’. Here, victory is measured not in seized positions but in shifts of public perception. Government units quietly monitor viral narratives, countering rumours designed to sap morale or sow discord between Tokyo and Washington.

The Arsenal of Commerce: Economic Statecraft in Practice

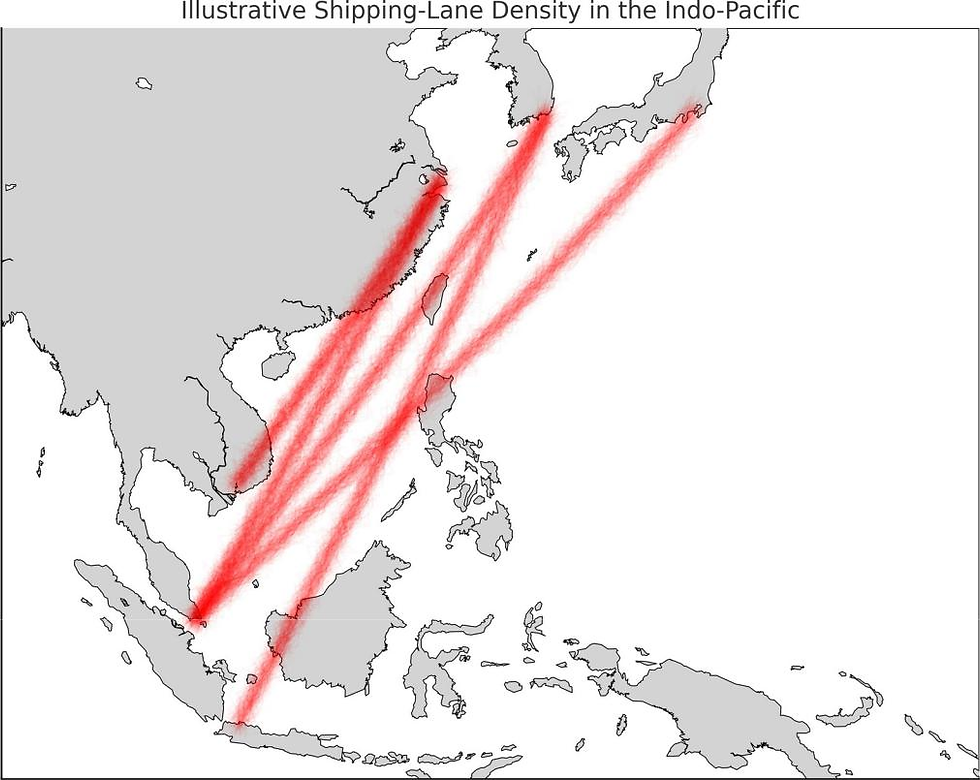

Underpinning the military build-up is an equally ambitious economic security agenda. For a country that imports nearly all of its energy and a significant share of its food, the spectre of disrupted sea-lanes is existential. Tokyo has therefore begun to treat trade routes with the same solemnity that earlier generations reserved for castle moats. It finances port modernisation projects in Southeast Asia, subsidises semiconductor fabs on home soil and amends legislation to allow the forced disclosure of supply-chain vulnerabilities. Where economists once spoke in the language of comparative advantage, policymakers now borrow the idiom of battlefield logistics: chokepoints, redundancy, surge capacity.

Possible Futures: A Short Strategic Fiction

Looking ahead, several storylines compete for plausibility. In the baseline projection, the United States remains committed to the Western Pacific, the PRC continues its grey-zone campaign around the Senkaku Islands, and Japan, having met its two-per-cent spending target, prudently invests in long-range standoff missiles and resilience-building civil defence.

A darker storyline emerges if Washington, distracted by domestic churn, threatens to pull back forces unless allies accept burdensome cost-sharing agreements. In that climate Tokyo might turn even more decisively toward Europe—inviting, say, a French amphibious group to train in the Nansei Islands—or, more controversially, it might accelerate dormant debates about nuclear options, even if only to sharpen

American attention.

The high-impact scenario, of course, involves Taiwan. Should Beijing impose a blockade, Japan would find its own fate intertwined with Taipei’s. Submarines would sortie from Kure, F-35s would scramble from Misawa, and the crisis would echo through global supply chains—semiconductor fabs in Hsinchu linking directly to car plants in Nagoya and Frankfurt. Yet escalation is not inevitable. The very interdependence of these supply chains provides a form of collective hostage, binding the fates of producers and consumers across continents.

Paths Forward: Narrative Recommendations

Policy recommendations unfold from the narrative like plot points from a well-seeded prologue. First, Japan would do well to treat its demographic decline not as a fixed lament but as an engineering problem—one solvable by selective immigration, automation and flexible reserve forces. Second, the cognitive front demands the same rigour that has long been lavished on the kinetic front: information-sharing agreements with European cyber agencies, scholarships for media-literacy programs in Southeast Asia, and perhaps a dedicated EU–Japan Centre of Excellence for Cognitive Security.

Third, European partners should realise that their own prosperity makes a brief detour through the Strait of Malacca before docking at Yokohama. Investing naval days and political capital in the Indo-Pacific is therefore enlightened self-interest, not distant charity. Finally, the United States, as the orchestra’s indispensable conductor, might codify its security guarantees in statutory language, insulating them from partisan oscillation and reducing the ambient anxiety of allies.

Final Thoughts

Japan’s story is not one of abrupt rearmament but of gradual awakening. Like the tide that creeps up a Shōnan beach, the change is almost imperceptible at first and then, all at once, undeniable. The nation is learning to live simultaneously within the American alliance and beyond it, to defend the homeland while also shaping a vast maritime commons, to invest in hardware without neglecting the software of public opinion. In doing so, Japan is not abandoning its post-war pacifist identity; it is redefining it for an age in which peace must sometimes be escorted by deterrence.

Whether this balancing act succeeds will depend on variables scattered across half the globe: U.S. election cycles, Chinese economic growth, European strategic autonomy and, not least, the voices of Japanese citizens who must decide how much of their budget, their attention and their collective psyche they are willing to devote to national defence. What is clear is that the choices made in Tokyo will ripple far beyond the neon quiet of its midnight streets, shaping the architecture of an Indo-Pacific order on which millions, from Hamburg to Hanoi, have come to depend.

Illustrative Figures and Map

Numbers and maps often speak a language more immediate than prose. The three visuals that follow are intended not as statistical exegesis but as narrative companions—snapshots that anchor abstract arguments in something the eye can measure.

Additional Thematic Maps

The following high-resolution visuals complement the narrative discussion by rendering two critical dimensions of geo-strategic reality: the crowded maritime arteries that sustain Asian and, by extension, global commerce; and the launch corridors that propel satellites into orbits upon which that commerce increasingly depends.

Further Granular Visualisations

Maps can distil thousands of data points into a single glance. The next two overlays focus on the infrastructural sinews—submarine cables and energy pipelines—that bind the Indo-Pacific economy together and, in doing so, add new layers of strategic vulnerability.

Comments